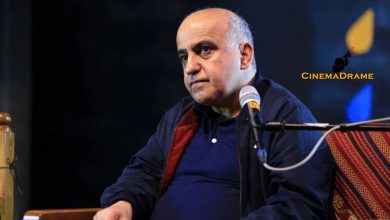

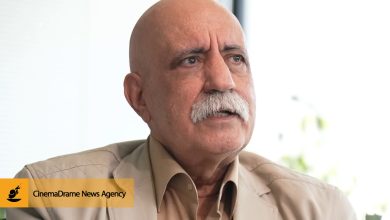

Loghman Madayen’s Critique of Saeed Roustayi’s Film / Leila’s Brothers in an Age of Intolerance!

According to CinemaDrame News Agency, film critic Loghman Madayen, in an exclusive commentary, reviewed Leila’s Brothers, directed by Saeed Roustayi—a film that stirred much controversy in Iran and was likened to a confrontation with the regime—and wrote: Leila’s Brothers has a multilayered screenplay. Though its dimensions may not be tolerated, it bears a merit that must be appreciated: a filmmaker who tries to speak through his film has chosen the most civil way to express his views. And if he is ostracized, the same message will echo through others—at a much higher cost.

I will forgo the film’s messages, as they have already been discussed in detail, and I do not intend to fan the flames. I will focus solely on its cinematic dimensions.

The screenplay condenses society into the miniature scope of a single family, addressing on one side the concerns of a traditional household and on the other, the broader spectrum of society—including women.

The opening moments of the film are gripping. On one side, it portrays the shattered economy as broken glass beneath the feet of workers who have found no support in the law, showing that certain forces deliberately provoke them to leave violence as their only option for reclaiming their rights. On the other, we see Leila’s strained and pressured face, representing the suffering women of society, who can do nothing but breathe and watch a tightly channeled path unfold before them.

The screenplay is built around narrative turning points. The first is when Bayram asks Esmaeil Jourablo to pay forty gold coins in exchange for taking the family’s grand patriarchal seat, launching the central conflict. The film’s climax arrives when truths are revealed: Leila has taken the coins, Esmaeil is dethroned, and the second turning point occurs when we learn that Esmaeil lied to coerce them into selling the pre-purchased shop, paying the price for his deceit.

The film’s dialogue is finely crafted—it doesn’t disclose information hastily, it avoids slogans, it builds tension, enhances the pulse of the narrative, and shuns redundant words.

There are plenty of subtle jabs, like the scene where Esmaeil tries to sway his wife in their room and says, “If we become the family elders, my obituary will read ‘Patriarch of the Jourablo family,’ and for you it’ll say ‘Wife of the Patriarch of the Jourablo family,’” mocking the widespread societal practice of omitting women’s names on obituaries, gravestones, and across bureaucratic systems.

Navid Mohammadzadeh’s character, Alireza, is initially portrayed as an anti-value figure. He cannot defend his rights, avoids those around him, and fails to maintain relationships. But gradually, he chooses to stand by his family and defend his rights, ultimately transforming into a positive value.

The planting, development, and payoff of the main characters are well observed. Each main character appears in at least three scenes or is discussed in depth.

The screenplay is laced with powerful suspense—moments where we believe Esmaeil will become the family patriarch, think the property deed is mortgaged to the jeweler, or expect Manoochehr to betray the family during a corporate appointment process that resembles a presidential seat: each new person pays off the debts of the previous and then empties the pockets of the next, choosing a successor for this lucrative sinkhole.

The main storyline revolves around a father whose personality symbolizes despotism, dictatorship, monopolization, and absolutism. He parades around the family with selfishness, and all the power he wields comes from the silence of family members who allow this decaying traditional mindset to make decisions for them. He sacrifices the family and their capital for his grandiose dreams, unaware that his encouragers merely aim to empty his pockets for their own gain.

Despite its multitude, the film’s subplots are well handled—such as the life stories of all five children, the repressed resentments within Esmaeil, Bayram’s capitalist nature, and the final subplot involving Haj Gholam and Gardash Ali Khan.

Given the screenplay’s multilayered and robust structure, if we focus on the layer advocating women’s rights, Leila is the film’s heroine. She is aware of the current situation and seeks the best solution for escaping it. But her father—the film’s antagonist—tries to derail her from reaching her goal, ultimately succeeding. This is the same father who urinates in the kitchen sink—the family’s place of sustenance—symbolizing how his actions have contaminated their livelihood. The same father who suffers from constipation, a metaphor for his obstructive political thinking.

If we shift to the layer encompassing society at large, Alireza—representing the elite—is a hero attempting to revive morality across various societal spectrums with a rational outlook. Meanwhile, Leila, the symbol of women in society, becomes the anti-hero who attempts to break taboos and change the status quo through costly demands. But the key point is that Leila is the flip side of the same coin as her father Esmaeil. Both try to impose their will on others—one through shouting and aggression, the other through pleading and persuasion.

The film employs color psychology. I will touch on only two examples: Alireza wears gray, indicating his compromising nature, high intelligence, and neutrality. Esmaeil, at the film’s end, wears white, suggesting he has stepped down from his patriarchal role and now sees himself as equal—not superior—to others.

The set and costume design accurately reflect each class, indicating thorough research and attention to detail. However, color palettes are lacking, resulting in widespread inconsistency in visual tone.

The découpage features unique scene and shot arrangements, which elevate the film’s rhythm. The camera effectively draws in the viewer, keeping pace with the tension-laden dialogue. Still, the number of shots per scene could have been reduced, and better framing and camera movement could have been employed. The choice of end-credit music is flawed—it begins brilliantly but loses its direction mid-way, derailing the musical narrative.

The symbolic object linking the entire film is the property deed—used by Esmaeil to manipulate the entire family and enforce his will. Perhaps it symbolizes those who, when their destructive actions are challenged, seek refuge in the specter of disintegration to silence dissenting voices.

The film’s ending shines with Esmaeil’s death. Alireza, as the family’s elite, sees the father’s death as the demise of a certain ideology and its invalidation within the family. But he tries to stage the scene in a way that normalizes it and makes everything appear natural.

The actors performed excellently, capturing the essence of the writer’s message and personalizing their roles with brilliance. They were not stiff in delivery, physically constrained, or tone-deaf to the meaning of words. Their speech felt sincere and avoided repetitive patterns.

The crucial point about Leila’s Brothers is that—aside from Leila—all family members, each representing different segments of society, still accept the father and his destructive mindset, and are unwilling to change. This is precisely why Leila and those aligned with her fail to achieve a desirable outcome.

In terms of character psychology, following Erik Erikson’s first stage of identity theory—trust vs. mistrust—Navid Mohammadzadeh’s character, Alireza, is a hesitant hero. Because of a dark past, he avoids committing to family responsibilities, unable to trust the very people seeking his help. He is a shadow-like figure who, scarred by life’s wounds, has learned to keep his distance. Ultimately, faced with an unavoidable challenge, he is forced to confront and resolve his identity crisis.

Leila, the rebellious heroine of our story, reflects Erikson’s second identity stage: she seeks autonomy and independence from her parents, revolting against her father’s tyranny. Yet lacking full freedom of action, she tries to involve her brothers and win their support. She wages an all-out battle for the independence of herself and her siblings—a path that proves impossible for the others, leading the audience to empathize with her and admire her resolve.

Esmaeil—the father—is afflicted by Alfred Adler’s theory of neurotic inferiority or superiority complex. His psychological disorder manifests in a pathological need to dominate and humiliate others. The deeper his inferiority, the more extreme his drive for superiority becomes, leading to compulsive overcompensation.

All critiques aside—kudos to the entire team behind this brilliant work.