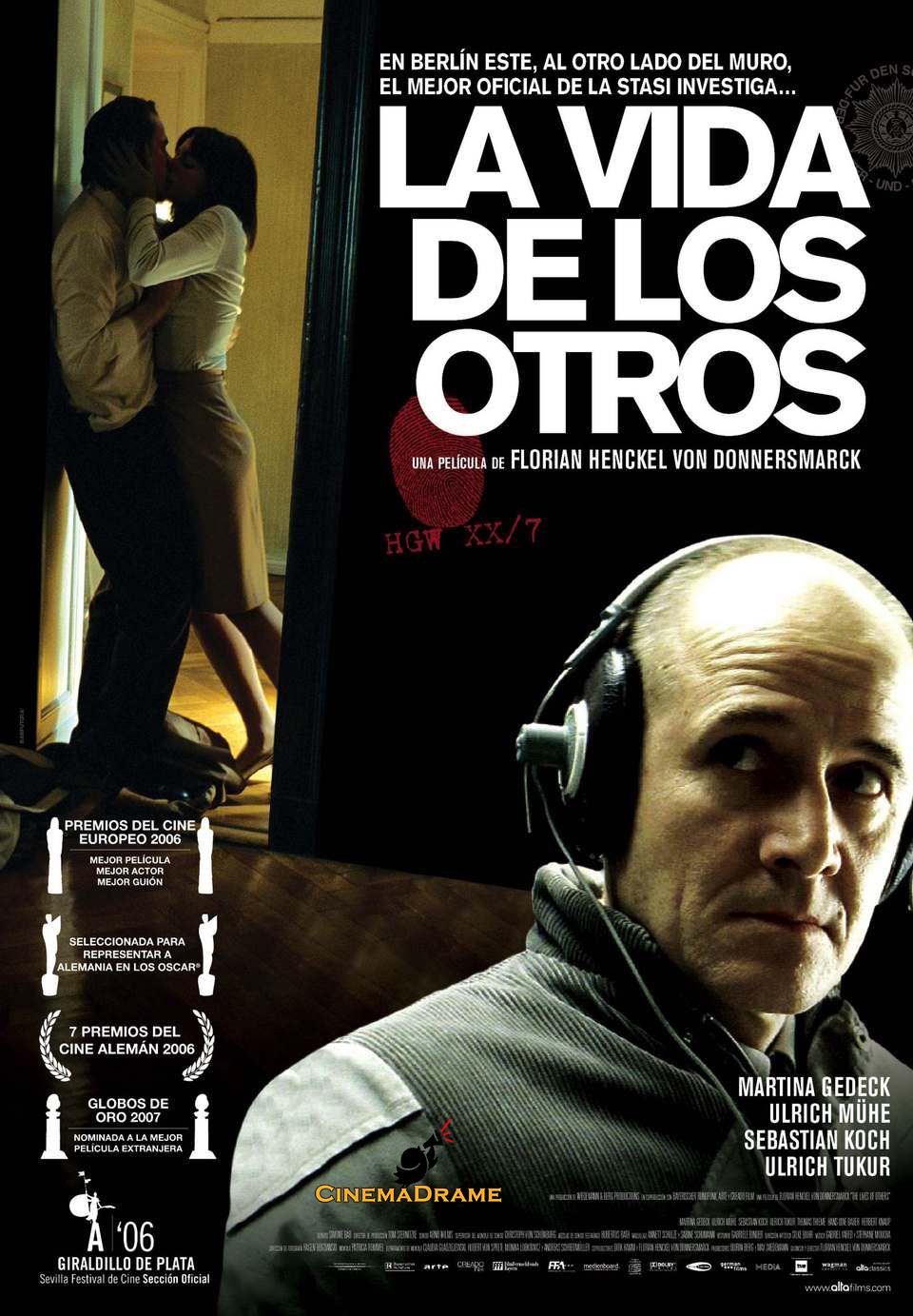

Loghman Madayen’s Critique of The Lives of Others: A Film of the Countdown to a Collapse

According to cinemadrame News Agency, Loghman Madayen, a film critic, penned an exclusive note on Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s film The Lives of Others, writing: “The Lives of Others” is the story of an aging Stasi agent who, after years of service, begins to tremble, fear, and falter. Trained under Soviet colonialism, he knows—deep in his bones—what in his communist regime is sacred, and what is profane.

It is a narrative of listening; a narrative of seeing; a narrative of thinking, and a narrative of doubt. It tells the story of a veteran Stasi agent in the German Democratic Republic—shaped by Soviet colonialism—who, after years of service, begins to tremble, fear, and falter. But not from abandoning his principles—rather from what he once believed in, once had faith in, once held hope in. He knows, with every fiber of his being, which parts of his communist system are sacred, and which are profane. He clearly sees that the nation’s ailment is not the pen of a writer, but the mismanagement of its high-ranking officials. He understands how effortlessly they fabricate cases; how they chain the art of artists; how they murder talent just to preserve their seats of power. He sees how, from the October 1917 revolution’s vessel, people are forcibly cast out. He is revolted when he sees the merciless claws of power turning a lover into a prostitute—one who belongs to no one. He sees all this, and does not stay silent. He knows his craft. He pays the price. And he remains in history.

Our character Wiesler does not play with words; he does not shut his eyes; he does not play politics; he does not silence the voice of his conscience; he does not shrug off responsibility; he does not justify; he does not become “just a functionary”; he is not “merely following orders.” He tears down the walls of his own dogma long before the Berlin Wall collapses. Before East and West Germany are reunited, his own beliefs are made whole. The film is set in a cold and stifling atmosphere—very much like the suffocating air of the Soviet era—and it portrays that regime with haunting accuracy: corrupt, crippled, rude, arrogant, terrifying, shameless, intrusive, obstinate, bold, and deeply afraid of anything that smells like thought. A regime that buys the mind of thinkers, the pen of writers, and the thought of dissenters—for cheap: for bread, for breath.

I enjoyed watching it, and here, I recount what I witnessed. A German film, the directorial debut of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, and winner of the 2006 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The film begins at the Security Academy, where Hauptmann Gerd Wiesler, senior interrogator of the Stasi, trains his students in interrogation techniques. The clever tricks used on suspects in interrogation add to the appeal of the film and reflect the writer’s deep research and mature script. Wiesler’s mission is clear: find any evidence of subversion in the subject—Georg Dreyman.

The film’s standout line comes when Wiesler tells a prisoner under interrogation: “Do you think we arrest people without reason? If you think our humane system would do such a thing, then that alone justifies your arrest.”

The first plot point emerges when the Minister of Culture forces the subject’s lover into a car and rapes her. When Wiesler reports this to his superior, he realizes the depth and banality of systemic corruption. The film reaches its apex when Wiesler’s superior, sensing his awakening, storms into Dreyman’s home without warning. The second turning point occurs when Maria, forced by fear, reveals the great secret, and just at the critical moment, Wiesler enters the home and alters the scene to orchestrate the Stasi’s greatest failure and save Dreyman from peril.

The film’s central object is a typewriter—used to type the most important report against the regime—one that challenges the Stasi and renders tracing the author impossible. Wiesler knows all the details but consciously looks the other way, and ultimately, Maria, haunted by the terror of betraying the typewriter’s location, dies unintentionally. The case is closed forever, thanks to Wiesler’s brave act of relocating the machine and ensuring it’s never found. Wiesler pays dearly for looking the other way.

At first glance, the film’s protagonist may seem to be a writer like Albert Jerska—banned from writing for seven years due to his revolutionary activity—or perhaps Georg or Maria. And the antagonist might be Wiesler himself, or his superior, or the Minister. But as the film unfolds, the role of hero gradually shifts to Wiesler, with his superior becoming the true antagonist. Interestingly, this same superior attends Wiesler’s lecture at the beginning and praises him afterward.

Wiesler’s sense of action and emotion is in stark contrast to Dreyman’s. To grasp this fully, consider the scene where Wiesler, after listening to Dreyman and Maria, attempts to compensate for his own lack of love by hiring a stranger for intimacy. This reignites his repressed desire. His inability to hold on to this woman parallels Dreyman’s pleas to Maria to stay with him.

The screenplay skillfully employs Brecht’s gifted book, presented by Albert, to create suspense and drive Dreyman forward. Though Dreyman always had a revolutionary spirit—eschewing ties in support of workers and discouraging books as birthday gifts, seeing them as symbols of intellectual pretension—Albert’s gift prompts reflection. He realizes the book can catalyze his transformation into an engaged individual. That same book is later taken and read by Wiesler, who, without permission, brings it home and is profoundly affected. The warmth between Dreyman and Christa-Maria, their knowledge and love, hasten Wiesler’s metamorphosis.

Other suspense elements are well-written and technically sound, adding allure—like when we’re unsure why Wiesler instructs the suspect to place his hands beneath his thighs and press his palms onto the chair. Or when he starts noticing the Minister’s interest in Maria. Or when he chooses not to report finding the whistleblower. Or the tense moment when he tries to coax Maria into revealing the typewriter’s hiding place.

In color psychology, Dreyman’s olive-green coat represents his resilience through hardship—the same resilience that allows him to witness his lover’s assault without breaking, to see his friends die and grow stronger, to see the ruling regime’s death cart and remain unwavering. The color symbolizes his openness to experience and capacity for growth—evident when he initially resists Albert’s book as a pretentious gift, then comes to see it as a catalyst for his evolution.

Maria Christa-Maria Sieland wears a brown fur coat and hat—symbolizing a family-oriented individual. In the film, she supports Dreyman through the darkest moments, keeping him grounded with her love, infusing warmth amid the cold. Her color hints at her sensitivity—shown when she endures rape yet holds herself together to protect Dreyman from harm.

Wiesler is mostly clad in gray—a color symbolizing his steadfastness in the paths he takes, his intellect and reasoning. When tasked with quelling dissent, he stands firmly; when he realizes his errors, he works earnestly to rectify them. His attire reflects his neutrality and conciliatory stance. Though an expert Stasi agent, he is politically naive. As he listens to dissenting voices, observes their private lives, and reads their work, he grows, and discerns honesty from cruelty. His sharp mind spots ideological contradictions. He sees the inner chambers of the political elite and realizes that his efforts for “security” have merely upheld the power of the corrupt. And he finds peace.

Three dominant colors pervade the film: dark green—conveying the regime’s paranoid surveillance and its envy toward dissenters; white—signaling the critics’ purity and the cold isolation of political life; and brown—evoking the steadfastness and maturity of dissenters, and their commitment to principle.

In Jungian archetypes, Wiesler embodies the shadow—a villain cloaked in law, torn by inner fragmentation. On one side, he bears the mask of a ruthless agent; on the other, he turns a blind eye to acts of liberation. This is the turbulent clash between his persona and shadow. Interpreted through Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, Wiesler first rejects the dissenters’ cause. When tasked with monitoring them, he crosses the first threshold. Deeply moved by Maria—the story’s temptress archetype—he refrains from reporting their “crimes” and merges with the father archetype. Later, by entering Dreyman’s home and removing the typewriter, he performs his ultimate act of compassion and pays the price. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, he is rescued by the people and reaches the final stage—freedom.

Maria embodies the anima—the damsel archetype, the symbol of romantic and erotic love. She exudes affection, sensitivity, kindness, and empathy.

Dreyman, in Jungian terms, is a self—constantly evolving, his expanding awareness reshaping his personality. In Adlerian theory, Dreyman is both Wiesler’s rival and—at the pivotal moment—his mentor, prompting Wiesler’s transformation and awakening.

The film’s subplots are meticulous—like the young man who breaks under interrogation, revealing Wiesler’s character and exposing the Stasi’s cruelty. Or the lustful gaze of the Minister toward Maria. Or when Albert visits Dreyman, preparing the ground for his ideological shift.

The film respects the rules of setup, development, and payoff—like the student who’s marked for dissent and reappears at the end near Wiesler’s desk. Or the surveillance equipment placed in Dreyman’s home that’s later discovered. Or the Minister’s lust shaping every interaction. Or Wiesler’s sacrifice for Dreyman that’s ultimately repaid. In the end, when Dreyman dedicates his book to his rescuer, Wiesler, we’re reminded of Nelson Mandela’s treatment of his jailer—the one who, when Mandela asked for a sip of water, would urinate on his face to humiliate him, yet, after the revolution, trembled with fear upon seeing Mandela in a restaurant, only to be invited to his table with kindness. Mandela said: “Don’t worry, we won’t do what you did to us,” breaking the cycle of revenge.

The film introduces its values and counter-values early on. In a scene akin to Hitchcock’s Rear Window, where Jeff gets into trouble for peeping into others’ homes, here Wiesler’s official duty is to spy on people—and from that very moment, his downfall begins, as he transforms from a force of oppression to one of redemption.

The film’s beauty is abundant—in the mastery of Wiesler’s surveillance skills, in the young boy in the elevator who nearly sends his family to ruin, and in the moment Wiesler’s transformation begins to reveal itself.

The final scene carries great weight. Wiesler, now stripped of his post, packs mail. Behind him stands the same man who, at the film’s start, had been dismissed by Wiesler for questioning the morality of Stasi tactics. Now, this former “undesirable” informs Wiesler of the Berlin Wall’s fall. Wiesler hears it on the radio through his colleague’s earpiece. What does this remind us of? Perhaps it’s the mirror to all the surveillance Wiesler once conducted. If all those wiretaps had worked, the Stasi should have sensed the fire beneath the ashes, heard the people’s pain, and sought a cure—instead of erasing the problem by erasing the dissenters. Now Wiesler, once the master of surveillance, hears the regime’s collapse as an ordinary citizen. Yet his quiet acts left a deep imprint—on Dreyman, on the cause of change, and ultimately, on the birth of freedom.

In terms of mise-en-scène and découpage, the production and costume design are precise. Wiesler and his colleagues’ appearances reflect the cruelty of the Stasi. They transport detainees in disguised fish-delivery vans. The Minister’s entire life is summed up in the scene of his assault on Maria—his only asset is his armored car, which represents his entire identity. Dreyman’s clothes reflect the intellectual writer; Maria introduces us to a luminous artist. Wiesler’s home matches his character—cold, soulless, plain, and austere—the opposite of Dreyman and Maria’s, which is filled with family, friendship, love, warmth, and the music of life and hope. When Wiesler listens to Dreyman’s piano, he cries and identifies with them—reminding us of Mandela’s words: “I pity the jailer, for each time he opens the hatch, I see freedom, and he sees the darkness of the cell.” And so, with each surveillance moment, Wiesler grows more aware of their truth and his own delusion.

The lighting is excellent—you feel the psychological torture in the interrogation room, the emptiness in Wiesler’s home, the cold white light of the surveillance station. The director knows where to place the camera, holds the viewer’s pulse, makes you feel the pain of prisoners, the anxiety of resistance, compels you to empathize with Wiesler, frightens you alongside Dreyman, and with a perfect ending, brings joy back to you as it does to Wiesler.

The film’s music, composed by Gabriel Yared and Stéphane Moucha, is beautiful. At the beginning, a joyful tune plays as Dreyman and Maria perform a subtle duet backstage before the Minister—a foreshadowing of the entire plot, which revolves around two individuals under the gaze of power. The music heightens tension at the right moments—like during the sudden raid of Dreyman’s house—and soothes as the mission fails. And in the tragic moment of Maria’s death and Wiesler’s downfall, we hear a death knell—her physical death, his professional one.