Critique by Loghman Madayen on Ali Abbasi’s film / “Holy Spider” targets ignorant pseudo-religious zealots, not religion itself! / It underscores the importance of media as the fourth pillar of democracy and defends the dignity and honor of journalists.

According to CinemaDrame news agency, film critic Loghman Madayen, in an exclusive commentary, reviewed and analyzed *Holy Spider*, the controversial film directed by Ali Abbasi, writing: *Holy Spider* became a sensational topic in Iran—ranging from fatwas issued against it to accusations of insulting the sanctity of the eighth Imam of Shia Islam—which propelled it to the headlines. You ask whether it intended to offend? I’ll say I can’t read minds, but as a viewer and a critic committed to Islamic principles, I can examine this film through my own lens. I believe this film seeks to say that in this seemingly religious society—where the Supreme Leader has repeatedly asserted how far it is from truly becoming Islamic—if people of faith truly acted upon divine commandments and the recommendations of the Infallible Imams, then no woman would turn to prostitution to feed herself and her child.

It aims to shake the sacred ignorance of the masses, to tear through the cobwebs that ignorant fanatics have spun over the framework of sacred law—webs that have diverted some from sincere religious concern toward using religion as a tool to ease their personal pain.

This is far from what Imam Ali (peace be upon him) pursued during his brief rule—which, by modern geographical terms, spanned 24 nations—as he sought to build an ideal Islamic society grounded in human-centric Qur’anic values. He sought to establish justice in a classless society, to eliminate all notions of “insider” and “outsider,” to hold everyone—from himself, the ruler, to the most common citizen—accountable under true law; to abolish all forms of slavery, to revive ethics in public life, to cut the hands of profiteers from the public treasury, to respect dissent. He instructed his intelligence service that even if they knew Ibn Muljam hid a sword under his robe, they had no right to arrest him before he committed a crime. He taught his prison guards that even if Ibn Muljam assassinated Imam Ali (peace be upon him), his rights as a prisoner must not be violated. Even those who waged war against him at Jamal were not declared apostates or enemies of God; they were considered mistaken rebels, and their blood was spared through dialogue. He even went a step further, sending Aisha, the wife of the Prophet—who had led an army and caused the deaths of 5,000 of the Imam’s companions—back to Medina with dignity, without placing her under house arrest, saying: “Let our judgment be with God!”

The film takes on those who want tears for consolation—not awakening.

It says you can be a Muslim, live beside the Imam Reza Shrine, and still remain ignorant of the profound verses of the Holy Qur’an and the life-giving teachings of the Ahl al-Bayt (peace be upon them). You can live far from the ideal Islamic society and spread the sacred ignorance you’ve adorned with religious coloring like cobwebs across the entire city—even over the shrine of an infallible Imam.

Another key theme of the film is its focus on the fourth pillar of democracy: the media. A journalist enters the story, walking the path of justice, risking her life to restore peace to a society terrorized by one individual—ensuring that he is held accountable by the law.

Her journey reflects verse 21 of Surah Al-Imran, which—according to interpreters like Ayatollah Taleghani (may God bless him)—refers to those who may not even believe in God or heed the prophets, but if they rise for justice and are killed along the way, God ranks their killer among those who murdered prophets. This verse reflects the sanctity and significance of journalism, as played by Zar Amir Ebrahimi, whose character takes that same path—knowingly or unknowingly—aligning herself with prophetic ideals.

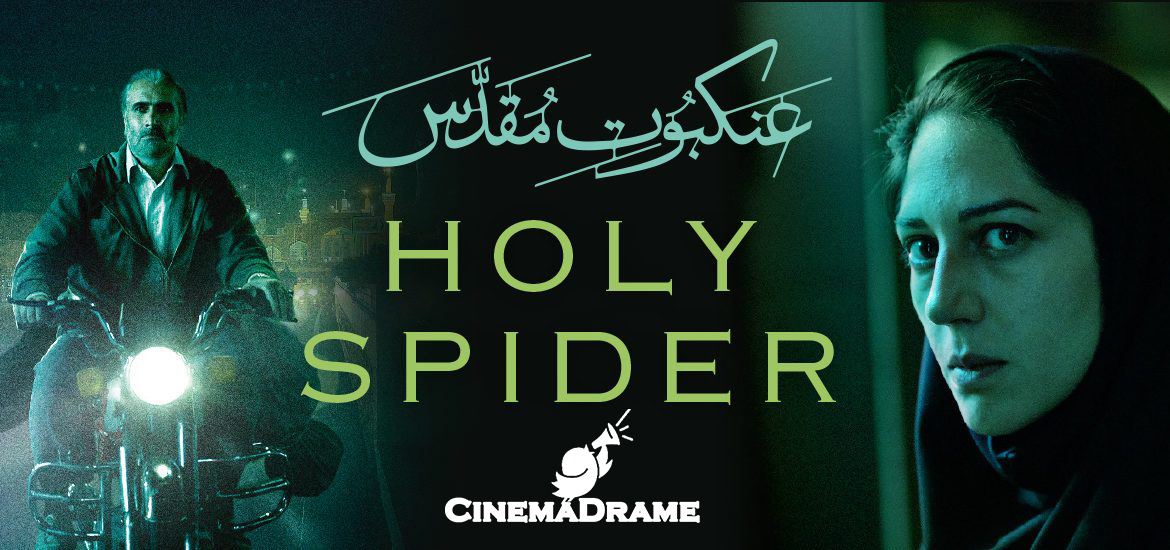

At first glance, the film appears to transgress the religious boundaries of the holy city of Mashhad. From the red agate ring on Saeed Hanaei’s right hand, the camera rises to a wide aerial shot of the Imam Reza Shrine. The city’s streetlights and highways are arranged to converge on the shrine, as the film’s title appears in bold. It may seem like an act of Islamophobia.

But I want to offer a different interpretation. The yellow light from Saeed’s motorcycle leads us to an aerial view of Mashhad, where all the city’s lights match his, and the street plans converge on the shrine, which sits at the center. To me, this imagery has only one meaning: the city is full of “Saeed Azimis” who have surrounded Imam Reza (peace be upon him), and the shrine—now lit in the same color as their lights—symbolizes how this sacred space has been overtaken by pseudo-religious fanatics.

Whether intentionally or not, the film becomes a defense of Imam Reza (peace be upon him), reminding us of his isolation. During his captivity under the tyrant Caliph Ma’mun, he would mourn Imam Hussein (peace be upon him), and pseudo-pious crowds would join his mourning and shed tears—yet fail to recognize that the very Imam sitting among them was just as oppressed and alone. They were near him, seated in his presence, witnessing injustice—yet as if veiled by ignorance, they neither heard, saw, nor thought. And eventually, that very Imam became the victim of their ignorance and the tyranny of the rulers.

This is where that Qur’anic verse resonates: “O you who believe, believe!”

Let me speak fairly: If you leave your house abandoned for a while and return, won’t you find cobwebs on the walls? It’s the nature of neglect. The same happens to the mind—if it’s not maintained with thought and contemplation, it decays into ignorance, dogma, and superstition, corrupting sound belief and damaging the mighty tree of thought. The only fruit it bears is sacred ignorance.

This directly echoes the Prophet’s hadith: “One hour of contemplation is worth more than sixty years of worship.” How true. He foresaw today’s dangers. Whether we call it *Holy Spider* or *Sacred Ignorance*, the result is the same. The issue is not the label—but the cobwebs that have paralyzed the human spirit.

And that is the film’s ultimate message: a people who have heard Islam’s voice but failed to understand it. A people who know the Ahl al-Bayt (peace be upon them) but not their mission. Who have clung only to the surface of Shi’a jurisprudence and ignored its depth. They’ve embraced the mourning but forgotten its purpose. One is reminded of the days when people sat in the presence of Imam Ali (peace be upon him) and asked: “How many hairs are on my head?” And Ali sighed at their ignorance.

Imam Sadiq (peace be upon him) beautifully summarized such people when he told Sadeer Sarraf—paraphrasing: “If sheep were sitting in their place, it would be more useful.”

So yes, one can be a Muslim and not a Muslim. A Shi’a and not a Shi’a. Be next to Imam Reza (peace be upon him) and still betray him. Is that not exactly what Saeed Hanaei and his many like-minded followers represent?

What’s the difference between people who see that girl, that pregnant woman, that mother forced into prostitution—and instead of helping, avert their eyes? Rather than confronting the causes of poverty and moral collapse, they draw blades against its victims.

The film beautifully shows that even the impoverished woman forced into prostitution holds to her faith. Night after night, she stands before the shrine, offering greetings to Imam Reza (peace be upon him), before heading off to sell her body to feed her child. Her faith may be stronger than that of the pseudo-religious, for in the darkest days of her life, she maintains reverence. And as for those religious pretenders—who knows how they’d behave in her place?

Didn’t the Prophet (peace be upon him) say: “Whoever sleeps full while his neighbor is hungry is not a Muslim”? Then how, in our so-called Islamic utopia, do “the very full” live side by side with “the very hungry”—as Martyr Beheshti said? And how could those who saw prostitution at the shrine’s edge not question their own Islam when, beside the pilgrimage of believers, a woman in abject poverty sacrifices her body to survive?

You say the government is at fault? Fine. Those who, in their ignorance, tried to erase the issue by creating “chastity centers”—each in their own way, like Saeed Azimi—yes, they failed. But what about the individual responsibility of each Muslim? Wasn’t it when the second Caliph asked what people would do if he deviated from justice, the crowd shouted: “We’ll straighten you with the sword!”—a testimony to the people’s agency in their society?

Just as Imam Ali (peace be upon him) said: “I fear the day when the oppressor calls for justice and the oppressed remains silent,” that day is now. That day is the film *Holy Spider*. It shows a people who are not just victims of government or clergy—but victims of themselves. Their silence has empowered both ignorance and crime.

Saeed Hanaei is not a lone killer. He is the product of a society that, instead of addressing the roots of suffering, builds shrines around murderers. The moment he is executed, people are seen lighting candles for him. His son, rather than ashamed, grows proud of his father. He sees him not as a criminal, but as a martyr. And journalists—the few who speak up—are either silenced, intimidated, or forced into exile.

The film neither insults the Imam nor the religion. It does not attack Shi’ism. Rather, it critiques the kind of deviant religiosity that hides behind the garb of faith. The kind that replaces introspection with slogans. That praises martyrs but forgets the meaning of martyrdom. That venerates the Ahl al-Bayt but lives in total contradiction to their teachings.

Those who accuse this film of blasphemy either haven’t seen it or have no understanding of what blasphemy actually is.

And if you ask: “Then what do you call that scene? That visual? That dialogue?”—I answer: Look beyond the literal. Don’t fall for the cobwebs of interpretation. There is a truth here that cannot be denied: We are losing our humanity. And what is Islam, if not a defense of humanity?

This film calls us to remember the Qur’anic verse: “Indeed, prayer restrains from immorality and wrongdoing.” So if your prayer doesn’t restrain you, it is not prayer—it is habit.

It reminds us that the Imam we mourn each year, the Imam whose name we shout in the streets, was poisoned by a system that claimed religiosity, just like ours today. The difference is, back then the people were oppressed. Now, many have become willing participants.

This film is not against Islam. It is against those who have emptied Islam of its content, leaving only rituals. Against those who recite the Qur’an but do not reflect. Against those who believe their outward piety compensates for inner decay. It is a defense of true Islam—just as it is a mourning for what we’ve lost.

It is a funeral for thought.

A eulogy for reason.

A last call for those who still care about truth.

So I ask you: If this film shakes you, good. Maybe your soul still breathes.

But if it enrages you, not because of falsehood but because of its piercing truth—then you are part of the very problem it reveals.