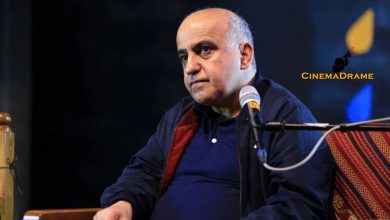

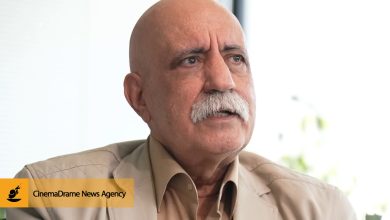

Critique by Loghman Madayen on The Covenant (2023) by Guy Ritchie, Marking the Anniversary of the U.S. Army’s Escape from Afghanistan

According to CinemaDrame news agency, on the anniversary of the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, film critic Loghman Madayen has penned an exclusive essay reviewing The Covenant (2023) by Guy Ritchie. He writes: The Covenant is one of the significant films of 2023. It revisits the story of the American retreat from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s return to power. The film clearly highlights those who collaborated with the U.S. for the promise of immigration, taking us to Afghanistan to portray individuals who, as interpreters and cultural advisors, were recruited by the U.S. military and served alongside them. Whether fighting the Taliban is good or bad is not the subject here—that’s a separate debate. The focus is the film’s ultimate message: that when the 100,000-strong U.S. army fled Afghanistan, it refused to evacuate any of the 50,000 interpreters it had contractually committed to relocating to the United States. More than 300 interpreters were killed, and thousands of lives were shattered. The American military was willing to fly back home with two trained dogs on board an empty plane, yet those who had risked their lives, families, and homes in service to them were left behind. This is yet another document revealing how the U.S. government exploits people as disposable tools.

The film powerfully depicts the American occupation: private military contractors, essentially professional mercenaries, receive a fixed fee and head off—fully armed—to bomb wherever they’re told, without regard for civilian lives or any obligation to inform the central government of their operations.

It shows how the U.S. military, based solely on a single report, allows itself to aim weapons at civilians. The film effectively illustrates the aftermath of collapse: a beautiful, resource-rich country ravaged by occupying forces, where some are now willing to cooperate with the occupiers just to survive. It demonstrates that toppling a regime achieves little beyond opening the floodgates for looting—leaving the people as the ultimate victims and the nation in ruins. Extremists, emboldened, no longer bother with appearances or restraint.

The film opens with gripping early scenes that swiftly pull the viewer into the story, making clear that we’re in for a powerful experience.

The central narrative pivots around a single, profound question: what if we didn’t exploit people? It portrays the bond between a commander specialized in so-called urban irregular warfare and his personal interpreter. When the commander realizes that, after the U.S. withdrawal, this interpreter—who had saved their lives multiple times—was abandoned with his wife and child, now in constant danger, he sets out to persuade the military brass to authorize their relocation. Yet no one takes responsibility. The commander now faces a pivotal dilemma: ignore the interpreter’s sacrifices and accept his likely death, or repay his debt and risk everything to save his life?

The film’s subplots offer essential insights. We quickly learn about John’s private life—his wife, his children—and understand that he has walked away from a normal life. We grasp the dire conditions of Ahmed, learn of his dark past, understand the pain that fuels his maturity, and realize the severe danger facing him and his pregnant wife. These and other detailed elements weave together to fully round out the story.

A major weakness of the script lies in its failure to honor the principles of setup, development, and payoff. Characters appear and disappear at will, with no respect for continuity or progression—this is a serious flaw.

The film’s key symbolic element is the passport: the very thing that convinced so many interpreters to risk everything in hopes of receiving it. And when the army refuses to uphold its promise, John is forced to act alone to save Ahmed and secure his passport.

Another shortcoming of the screenplay is the absence of a character who undergoes a true transformation—from virtue to vice, or vice versa.

However, the dialogue is one of the screenplay’s strengths: short, fluid, simple yet engaging, mysterious and tension-driven, never over-expository, laced with humor and suspense. The screenwriter demonstrates deep knowledge of customs, dialects, and vocal nuances, and skillfully advances the story without relying on easy reveals.

The film’s first plot point occurs when Ahmed earns John Kinley’s trust—after extracting a confession from a terrorist, unmasking a traitor, and saving eight lives—leading to a new mission that will profoundly test him.

The climax unfolds when John hears from a friend that Ahmed, after saving his life, has become a local hero. The Taliban, branding him a traitor, have added his name to a top-ten most-wanted list. Now in hiding with his family, Ahmed is a fugitive. The truth is laid bare, and John realizes the military has betrayed its promise. He accepts that it is now his personal duty to intervene.

The second turning point comes when Ahmed agrees—once again—to entrust his and his family’s life to John and rely on the U.S. army. They set out, and the story moves toward resolution.

The film’s hero, John Kinley, embodies the archetype described by Rollo May: a lone cowboy-warrior, courageous and principled, capable of restoring justice and order in chaos, excelling in urban combat. A self-reliant individualist, he needs nothing but his gun and a car, and in the end, he rides off into solitude. His mentor is Ahmed, whose authentic self-sacrifice breathes new life into his people. Inspired by Ahmed, John gives up everything in defense of a sacred ideal.

The antagonist is the Taliban. They initially target John and his team, but after being outmaneuvered by Ahmed’s cleverness, they shift focus to him, seeking to eliminate the threat. They constantly place obstacles, diverting Ahmed and John from their path. Following Rollo May’s theory, they represent the gangster-style anti-hero archetype. In their city, there is no safe place to hide. They exploit the people and fill the city with traps to ensnare the hero.

The film’s mise-en-scène is one of its most professional elements. Everything is top-tier. The set design is meticulous and thoroughly researched, grounded in cultural and social realities. It portrays a believable military base, complete with authentic airports, vehicles, and local cars. The depiction of homes, streets, and traditional markets is strikingly accurate. The costume design is admirable—the military uniforms are well-chosen, the hero’s wardrobe is imposing, and the superb makeup enhances the uniqueness and memorability of the characters.

The performances are another highlight. Every role feels personal, deep, and meaningful. There is no physical stiffness or verbal rigidity. The actors act freely and naturally, aligning their voices and body language with the script’s core themes. The local characters speak native dialects fluidly and sincerely, expressing their lines with facial expressions that match each scene. They give their characters dimension and avoid cliché performances.

As for the découpage, the film’s main directorial weakness appears in its ending: rather than refining the screenplay, the director resorts to a supernatural and overly Hollywood-style finale. A film that had shined with its simplicity is ultimately marred by artificial excitement. Still, the sound design is excellent, with music that enhances key emotional moments. The editing is highly professional—scene and shot placement accelerate the pace and energize the film. Lighting is carefully executed. Camera placement, movement, angles, and shot sizes are all meticulously calculated.