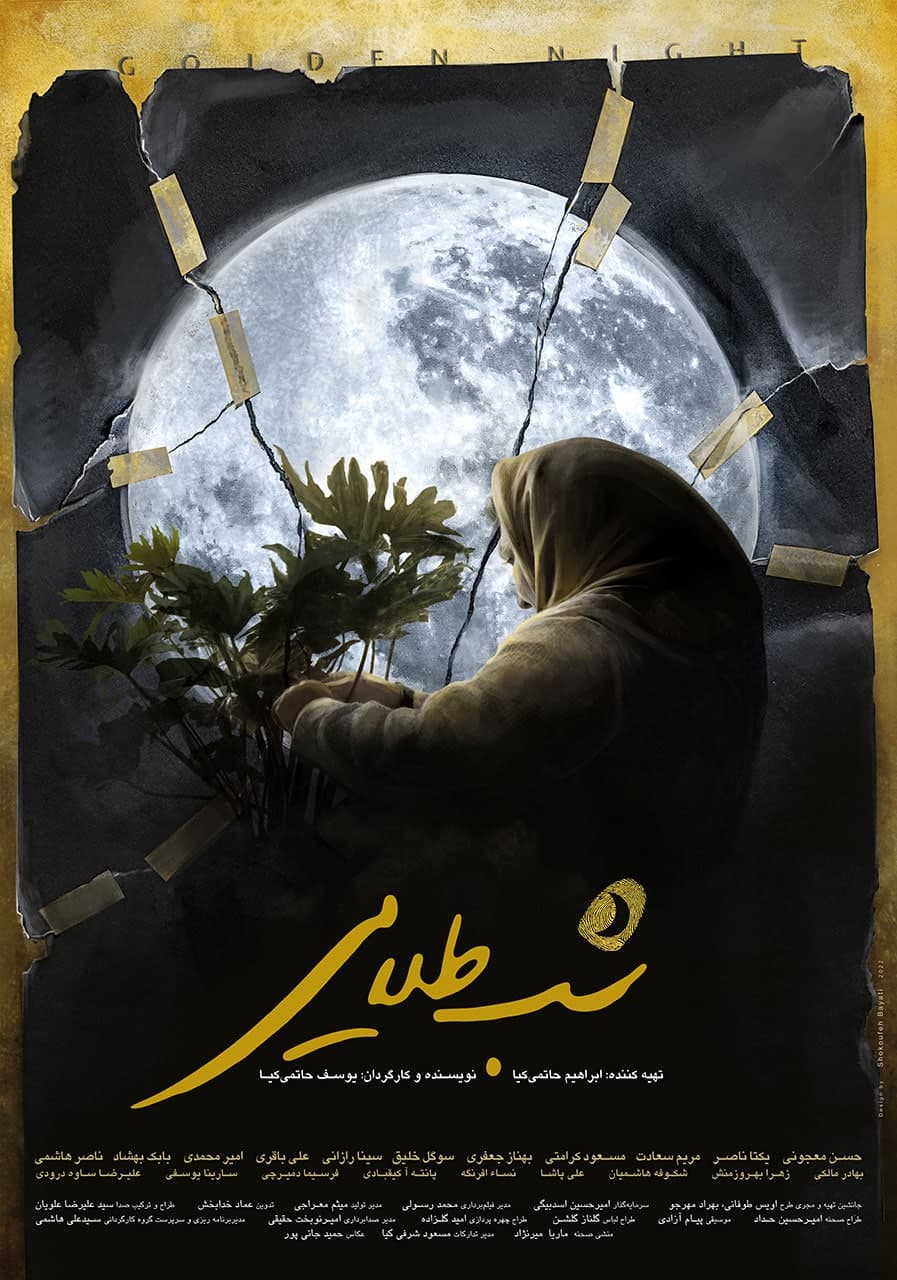

Hatami Kia’s masterpiece, stronger than the timeless work of August: Osage County.

Loghman Madayen, film and television critic.

Golden Night is a rich film, with a timeless screenplay, filled with effective suspense, well-crafted dialogues, and meticulously shaped subplots. The actors give outstanding performances, and the director has appeared very professionally on the field. The film has something to say, defending the essence of family values, showing that for the older generation, money was the least important thing, while for the current generation, it is just as important. It speaks about changing tastes, lack of patience and forgiveness, the importance of the thread of beads or the elder around whom everyone gathers, domestic violence, and its roots in the past, and the revival of the culture of trustworthiness, ultimately declaring that family is everything.

The film begins with the impressive entrance of Maryam Sa’adat, quickly pulling the audience into the heart of the story. Thus, we witness a very good initial few minutes.

The film can be viewed from two different angles, each defining a separate hero, showcasing the writer’s skill. On one side, there’s the story of a grandmother who believes her home is safer than a safe deposit box, and no thief would enter her house. Consequently, she pays the price of her trust by selling her house.

On the other side, the story of Faramarz, the family’s grandson, who is devastated by a heartbreaking love failure and, upon understanding the reasons behind it, holds all family members accountable and sets out for revenge.

The film features exceptional subplots, delving into almost all the characters, revealing details about their lives without overwhelming the audience with a flood of information. This approach is a professional move, considering the numerous characters in the film.

The hero of the film, from one angle, is Zahra Khanum, the grandmother, who tries to patch up the family and maintain their unity, ensuring that none of them turn into thieves. In the end, she pays the price for her trust by consenting to build the house.

From another angle, Faramarz is the hero. He is the one whose romantic relationship is ruined by Hamed, and his entire family, including his father, watches him suffer in silence. Now, he intends to take revenge on them all for this unjust destruction of his life. He confronts his uncle Ali in the yard, telling him that they are all responsible for the breakup. There, he draws a line between himself and the family, betrays the trust of Golbarg, who had been trying to win him over, and seeks revenge on her as well.

The first turning point of the film occurs when Hamed, in the yard, stops the family members from leaving and declares that no one is allowed to leave the house until the gold bars are found. It is revealed that these bars were the family’s shared investment, entrusted to Hamed to launch a production line, making them all stakeholders. This sets the stage for Faramarz to seek revenge.

The film peaks when Golbarg admits that she moved the gold bars in protest against her father Hamed’s behavior and her mother’s victimization, thus clearing Faramarz from the theft accusations.

The second turning point occurs when Zahra Khanum, the grandmother, tells her eldest son Mohammad that if he helps solve Hamed’s problem and keeps him out of prison, she will allow the house to be built, and life will return to normal. Faramarz then takes the gold bars out of the house, along with the flowerpot his grandmother had given him.

The unifying element of the film is the gold bars, which the entire family has a share in, and for which they fight among themselves. These bars provide Faramarz the opportunity to take revenge on the whole family.

The film has well-calculated suspense, such as when the grandmother grows suspicious of her younger brother Ali and tries to find out how he financed his new car, or when they search Raouf’s bag and find no gold bars, or when the police detective handcuffs Faramarz.

The film follows a careful structure of character development. Each character is shown at least three times in the film, and we learn about the situations they face without overwhelming the audience with excess information. Nothing is introduced without preparation, and even though the police detective enters the scene unexpectedly toward the end, his presence is so well-done and powerful that the lack of setup does not feel noticeable.

Faramarz starts as a man of values, who, after being sacrificed in a love story, shoulders all the sorrow alone. But gradually, when he realizes that there was a deliberate plot behind his heartbreak and that Golbarg played a part in this tragedy, he decides to betray her trust, just as she betrayed his, by moving the gold bars and taking revenge on her and his father Hamed. Here, he transforms into an anti-hero.

Another strength of the film is that the resolution doesn’t come from the writer, but from the characters, who, through their ups and downs, drive the story forward.

The dialogue writing is excellent: short and concise, simple and fluid, revealing information without overwhelming the audience, creating a sense of depth, maintaining mystery, and avoiding being overly explicit or tiresome. The dialogue also includes elements of humor, which enhances the strength of the lines.

With extremely professional direction, Yousef Hatami Kia has skillfully coordinated the camera with his creative mind, choosing the best spots for the camera and moving it at the right times and places. He knows how to frame images, has employed precise editing to keep the pacing of the film consistent, and has selected appropriate sounds for the scenes, such as the grandmother’s hearing aid amid the chaos or the music listened to by Mohammad’s grandson. The lighting is also a strong point, as it effectively conveys the warmth of the grandmother’s home and prevents visual fatigue, while the music for the opening credits reaches its climax with the same calmness as the film, mirroring its tension and resolution.

The director’s art lies in capturing all images within one house, making them feel fresh and non-repetitive despite the fixed location.

The film also incorporates color psychology: Zahra Khanum’s white dress symbolizes purity, calm, and innocence, reflecting her peaceful nature, and her role as the moral compass of the family. Mohammad, the eldest son, is represented by a green sweater, symbolizing hope, responsibility, and generosity. Hamed, with his black sweater, represents mystery and secrecy, while Golbarg’s red scarf signifies hasty decisions and her emotional, extroverted nature.

In terms of character psychology based on Carl Jung’s model, Zahra Khanum represents the goddess archetype, the nurturer and emotional backbone of the family. Mohammad embodies the wise old man archetype, offering guidance and leadership. Golbarg embodies the trickster, using deceit to manipulate Faramarz’s thoughts. Faramarz and Hamed serve as hero and anti-hero, with Faramarz symbolizing ethics, kindness, and peace, while Hamed represents corruption, cruelty, and violence. These two characters complement each other, and in the end, Faramarz must adopt some of Hamed’s negative traits to overcome him.

The performances of all the actors were brilliant. They were exceptional, showing freedom and independence in their actions, performing with soul and meaning, and going beyond their typical roles. Their body language and voice matched the script perfectly, creating a realistic and emotionally resonant performance.

The set and costume design matched the cultural context of the story, and great attention was paid to the personality, age, and worldview of each character. The props were meticulously chosen to fit the grandmother’s character, and the makeup of Maryam Sa’adat was outstanding.