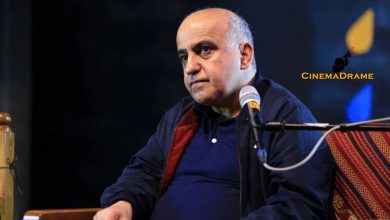

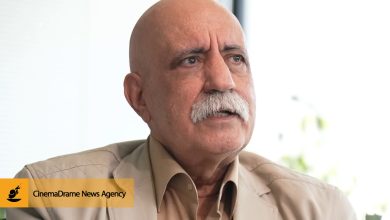

Loghman Madayen’s Critique on Houman Seyyedi’s Film / World War III and the Rage of the Powerless!

According to CinemaDrame News Agency, film critic Loghman Madayen, in an exclusive commentary, reviewed World War III by Houman Seyyedi and wrote:

Seyyedi’s brilliant work—winner of three awards for Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actor at the Belgrade Festival—is the same film that, after much hardship, was granted only a few days of domestic screening during the Oscar season.

World War III presents a comprehensive chapter of social psychology. It arrives to show us how the purest, most honorable, most virtuous, and most humane individuals can transform into terrifying Hitlers. It aims to illustrate where the story of mass anger begins, how harmless people are led—by a single foolish decision—down a one-way path, who fuels violence, and how a single explosion can reduce the flesh of people, whose hearts brimmed with love, to ashes, while those responsible for that blast evade accountability by abusing power.

The film depicts the oppressed masses whom the powerful refuse to hear—treating them however they wish—much like the persecuted Jews in Nazi camps, where our story’s Hitler watches them through a secure enclosure, mere steps from death.

The film is a cry from the depths of the powerless—a piercing echo of their pain. As Shakib says: “It’s easier for you to beat me than to hear what I’m saying.”

It speaks of women forced to live in a seemingly beautiful place, yet in its darkest corner—like a coffin—where they can neither speak nor hear.

The film touches on reciprocal violence, a non-existent judiciary, justice that isn’t allowed to be shouted for, and a system in which no institution listens to the people’s voices. When their last threads of hope are severed and they realize the entire system stands against them, each one of them becomes a merciless Hitler—responding to force with fury. This transformation is palpable in the film, especially when Shakib realizes he has fallen victim to authoritarian boots, that his voice will never be heard, and that no justice will ever reach out to him. He becomes a Hitler he himself doesn’t recognize—taking revenge on everyone, striking both guilty and innocent with the same hand.

The film skillfully portrays how a harmless man turns into a dangerous figure. It emphasizes the vital necessity of maintaining public hope in judicial, regulatory, and governing institutions, beautifully illustrating that the rage of the masses is far stronger than any institutional force, and shows how they are compelled to play into the hands of power—barbing themselves in with their own hands.

The film’s first plot point is when Shakib agrees to take Ladan to the filming location—where the story’s conflict begins.

The climax is when Shakib discovers that Saeed has deceived him and within one night erased all evidence of the explosion—then and there, Shakib screams and exposes the truth for all to see.

The second plot point unfolds when Saeed tells Shakib that legal avenues are futile—because, according to the contract, the court sides with the film crew and not with Shakib. Moreover, 63 people testify that he knew the house would be blown up. In that moment, Shakib sees everyone in that crew as his enemy and sets out for revenge.

The symbolic object linking the story is Ladan’s bangle. The girl who once shared her time with Shakib in exchange for money now gives him her only possession—her bracelet—to buy freedom. But it becomes the only trace of her existence, proving she did not run away, but was killed in the house.

The opening minutes of the film are effective, offering insight into Ladan’s character while introducing the crisis in Shakib’s life.

Shakib starts as a hardworking laborer and a morally upright man—a symbol of virtue—but gradually, under the weight of emotional trauma, he turns into an anti-value.

The film’s dialogue is exceptional—intelligent, non-expository, concise, and filled with tension. It balances humor and seriousness, while most importantly, preserving the film’s rhythm.

Suspense is meticulously crafted—like when we suspect Hassan has discovered Shakib is hiding Ladan, or when we fear the criminals will take Ladan away, or when we wonder if, based on her past, Ladan might still be alive. These moments surprise both the viewer and the protagonist.

The main plot revolves around Shakib and the hidden presence of his fiancée, Ladan—a strong plotline that effectively plants, cultivates, and harvests character arcs across at least three sequences. The subplots are also well executed—such as Saeed’s financial dealings, Hassan and Ladan’s lives, Shakib’s past, and the criminals who sought Ladan.

Shakib is the film’s hero—he chooses to disrupt the power play, refuses to bow to oppression, stands for his rightful claim, and in self-sacrifice, distances himself from fear to find peace.

The antagonist is Hassan—who, throughout the film, tries to oust Shakib from the project and ultimately destroys the explosion scene, removing Ladan’s remains and blocking the path to truth.

The mise-en-scène is a masterpiece of cinematography. Shot sizes are precise, camera placements are exact—like when we see Ms. Zareh and Shakib behind fences, or when Saeed and Shakib appear as two silhouettes against a dim light in a tent. Sound choices are deliberate, scene and shot order are well-arranged, and pacing is kept brisk. The screenplay is tightly edited, with actor dialogue carefully directed. No scene feels redundant.

Character psychology draws from Carl Jung’s archetypal model, the quaternity—Persona, Shadow, Anima, and the Wise Old Man—manifested in Shakib as the Hero, the Villain, the Lover, and the Mentor. He encounters each archetype in the story and absorbs aspects of them—confronting his flaws and challenges, like when he’s desperate to save Ladan at any cost, or when he reveals his deepest wound: losing his family in an earthquake. He learns revenge from his mentor, Hitler, and briefly claims his lover. From her, he learns to fight for a loved one, choosing resolve over escape. His strategic transformation occurs when, through abrupt identity shifts, he crosses a line.

The greatest strength of the World War III screenplay is that it ends heroically despite its tragic nature.

Set and costume design are highly intelligent. The use of color palettes aligns with lighting and avoids visual fatigue. Costume design reflects the characters’ cultural class and matches their professions.

Color psychology is present—a red house signals romantic tension, looming danger, and an adrenaline surge enough to trigger rage. Shakib wears a green jacket—symbolizing his passion for life, loyalty, calm demeanor, and revolutionary spirit. Ladan’s red scarf, framed with the red house in the same shot, signals imminent threat and marks her as the flame igniting love and danger alike.