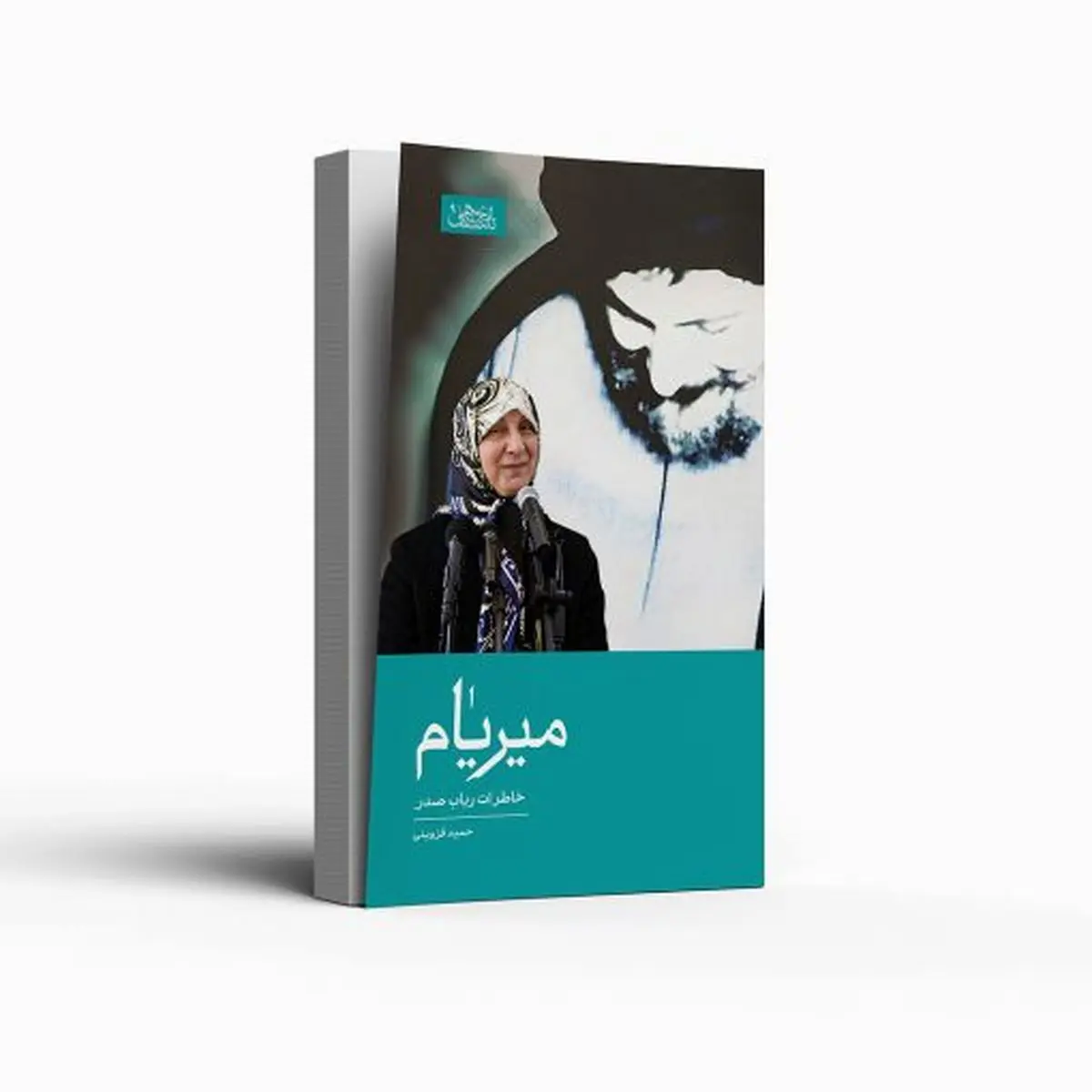

The Book “Miriam” (Memoirs of Robab Sadr, Sister of Imam Musa Sadr) Released

According to the Cinemadrame News Agency, oral history and the publication of personal memoirs are among the most engaging literary genres, capturing the attention of many publishers and enthusiasts of historical subjects.

A key characteristic of oral history is its ability to provide new or previously untold information from the perspective of individuals who were active participants, witnesses, or well-informed observers of historical events. This information is meticulously gathered and published through targeted interviews.

The recently released book Miriam chronicles the memoirs of Robab Sadr, Imam Musa Sadr’s sister. It delves into her life’s journey across more than five decades, touching upon her political, social, and cultural involvement.

For the first time, Miriam shares details about the abduction of Imam Musa Sadr, recounted by a family member. The book covers the days surrounding the incident, the subsequent pursuit of the case, meetings with heads of state, discussions with officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and the ongoing developments of the case in recent years.

Imam Musa Sadr, a prominent Iranian cleric and the leader of Lebanese Shiites, traveled to Libya for a meeting with Muammar Gaddafi, then the head of the Libyan government. On August 31, 1978, he was abducted and taken to an unknown location.

In Miriam, Robab Sadr provides her perspective on the reasons behind Sadr’s abduction and the movements and countries implicated, in response to questions posed by Hamid Qazvini, an oral history researcher and the book’s author.

An excerpt from the book details the ongoing efforts to follow up on Imam Musa Sadr’s abduction:

“The issue of my brother has always been raised with Lebanese presidents, dignitaries, officials of Arab countries, Iranian officials, and wherever I’ve gone. However, as time passed, hearing about it became less palatable for them. But we kept saying it, and we still say it; the judicial case remains open, and Agha Sadri (Imam Musa Sadr’s son) continuously pursues it.

Let me mention something here. From the day he was abducted until 1998 or 1999, no one spoke up. That is, a person like Imam Musa Sadr, who could free anyone from any prison with just two words, when he himself went to prison, there was no one to free him.

In my opinion, a person is religiously and morally responsible in their own life; they cannot remain silent. If they remain silent, they have sinned, according to the saying of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH): ‘The silent about the truth is a mute devil.’ Perhaps some people justified themselves, saying there was nothing they could do; but such excuses cannot absolve one of responsibility.

Once, when I saw that no one was paying attention to us, in Beirut, I, along with Imam Musa Sadr’s wife, went on a ten-day hunger strike. People gathered around us. When they saw us, their hearts were reassured. At that time, Mr. Bani-Sadr was the President of Iran. Through the Iranian ambassador, he sent a message to end the strike, stating that they would seriously pursue the matter. I didn’t believe him; I thought these words were false. Abu Ra’ed (my husband) said, ‘Be careful, you must preserve your dignity; don’t say that, accept it. You must uphold the Seyyed’s honor; people will eventually tire.’ Eventually, we ended the strike, but still, nothing came of it.

In your opinion, what was the most significant flaw at the beginning of the incident?

From day one, there should have been powerful forces supporting this cause. Unfortunately, it coincided with the weakness of the Lebanese government, and other countries had no motivation to pursue it. Additionally, we were not a political family; we are a religious, social, and service-oriented family, dedicated to serving the people. We didn’t know how to navigate political strategies or send someone to influential individuals. At that time, others also interfered with our decisions. Everyone offered advice, saying ‘do this,’ ‘don’t do that.’ At times, we almost lost sight of our own judgment.

Were there no influential friends or relatives who could offer help?

In Lebanon, we had no relatives. Some of the Imam’s friends were in the government or parliament, all of whom either concealed something from us or knew themselves that their efforts would not yield results. It’s like someone pursuing a path, knowing it won’t lead to their destination.

Is it true that Dr. Mostafa Chamran had ideas for the Imam’s freedom but didn’t have the opportunity to implement them?

In the very first weeks, he had ideas and was eager to do something; but cooperation was lacking. The group in Lebanon responsible for this issue had severe disagreements and did not agree with Dr. Chamran.

He held responsibilities in Iran after the Revolution. Was he still pursuing the case then?

In the very first days after he went to Iran, he became Deputy Prime Minister and later took over the Ministry of Defense. Ultimately, he was passionate and expressed frustration and sadness that few people were truly listening. When we went to Iran to pursue the matter, he was very happy. He hoped that things would eventually progress, but unfortunately, they didn’t. Soon after, Saddam’s war against Iran began, and he went to the front…”

In addition to these revelations, the book offers a fluid and cohesive narrative of Robab Sadr’s personal and social life, which is both compelling and distinctive. It’s compelling because the text is simple and unpretentious, faithfully preserving the narrator’s language and tone. It’s distinctive because it provides a rarely seen portrayal of a prominent Shia clerical family and a young woman from Qom, Iran, whose life journey led her to Lebanon, where she settled after marriage. Robab Sadr began her social activities in her early youth, and despite various obstacles and challenges, her efforts grew day by day. She never ceased her endeavors, even during the years of the Lebanese civil war and occupation.

Miriam is structured and written in seven chapters:

- For the Brother: Addresses the abduction of Imam Musa Sadr and the efforts to follow up on the case.

- For Kindness: Covers Robab Sadr’s childhood and adolescence, and her life in Qom.

- For Hope: Dedicated to how she journeyed to Lebanon, settled there, and began cultural and social activities alongside her brother.

- For Life: Focuses on Imam Musa Sadr’s efforts to promote coexistence among followers of different religions and religious sects.

- For Peace: Discusses the years of the Lebanese civil war and Imam Musa Sadr’s tireless efforts to establish peace.

- For Freedom: Explores the establishment of resistance against Israel and the defense of Lebanese territory.

- For Humanity: Details Robab Sadr’s activities in managing educational and social institutions that were founded in her brother’s absence and named in his honor.

Qazvini regards the book Miriam as the portrait of a woman who, relying on the ideas and actions of a progressive cleric, has persevered in her efforts to educate, promote health, empower, and improve the lives of girls and women, despite various problems and obstacles in a region of the Middle East where crisis and instability are rampant. From the author’s perspective, the book is also a valuable resource for those interested in women’s studies.

Miriam is the culmination of 32 interview sessions conducted by Hamid Qazvini with Robab Sadr in Iran and Lebanon between 2012 and 2022. It is the ninth volume in the oral history series of the Imam Musa Sadr Cultural and Research Institute, comprising 662 pages and priced at 415,000 Tomans.