The ninth session in the Sohrab series of specialized meetings was held, focusing on the critique and exhibition of the painting Tree of Life by Samaeh Sharifi.

According to an exclusive report by the CinemaDrame News Agency, the ninth session in the Sohrab series of specialized meetings—focused on the critique and exhibition of the painting Tree of Life by Samaeh Sharifi—brought together researchers and enthusiasts of art and mythology at Lajvard Gallery in Tehran, the capital of Iran. The “Sohrab” sessions, founded with the ideal of youth-oriented perspectives and approached through the lens of mythological studies, aim to present, critique, and analyze artworks inspired, even in passing, by Iranian myths. Through this, they seek to identify—and consequently introduce—emerging young artists, while challenging the tradition of “Sohrab-killing” as a core principle of cultural regression.

These sessions are organized by the Mit-Okhteh Center for Mythological Studies, affiliated with the Art and Architecture Research Group of Peydayesh, in collaboration with the Iranian Book Illustration Institute, hosted by Lajvard Gallery, and financially supported by Chaghalash Internal Periodical; Chaghalash Consulting Engineers Company. They are held once a month.

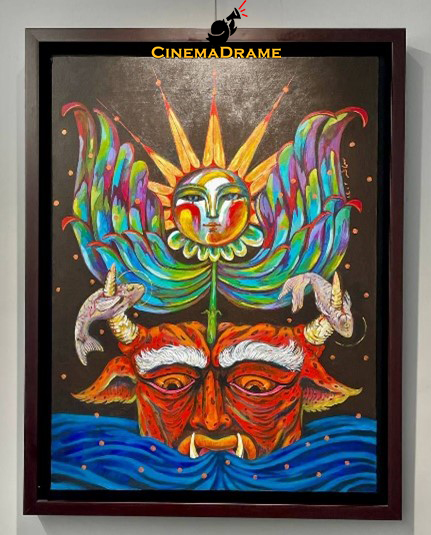

The ninth session was devoted to the critique and presentation of the painting Tree of Life by Samaeh Sharifi. The session’s moderator and expert, Mr. Maziyar Akhoondi, a member of the Mit-Okhteh Center for Mythological Studies, welcomed the audience and introduced the artist. Samaeh Sharifi, an illustrator and painter, holds a bachelor’s degree in Graphic Design from Al-Zahra University and a master’s degree in Illustration from the University of Art in Tehran. Her master’s thesis focused on symbolic illustration of the works of Suhrawardi. She has illustrated over thirty children’s books and participated in numerous exhibitions.

In this session, she explained that, in creating any work of art, three fundamental questions always accompany her: What am I painting? Why am I painting it? What am I painting it with? She emphasized the importance of research prior to creation, the presence of an Iranian tone in design, and the need for every element in her work to hold meaning—even if the audience does not perceive it.

Sharifi went on to describe her creative process in producing Tree of Life, noting how her encounter with mythological narratives—especially the classes of Dr. Avozpour—transformed her artistic path. She recounted her personal experience of the Tree of Life motif in Iranian mythology, explaining how the tale of the tree and its two guardian fish defending it from demonic lizards seeped into her subconscious. One day, upon seeing images from the war in Gaza, she was struck by the visual resemblance between shrouded infants and fish. This vision brought the myth to life in her mind, compelling her to create a work in which the guardian fish of the tree have been slain.

In the second part of the program, Mr. Akhoondi explained that the artwork would next be examined from three distinct mythological perspectives, and proceeded to introduce the speakers along with the themes of their talks: first, Ms. Nastaran Hashemi, a member of the Mit-Okhteh Center for Mythological Studies, speaking from a “descriptive mythology” perspective; then Ms. Saina Mohammadi Khabazan, senior researcher at the Peydayesh Art and Architecture Research Group, presenting from an “analytical mythology” perspective; and finally, Mr. Behrooz Avozpour, head of the Peydayesh Art and Architecture Research Group, offering an “archaeo-mythology” perspective.

Before Ms. Nastaran Hashemi began, Mr. Akhoondi introduced the book Myth and Mythology according to Georg Friedrich Creuzer: Allegorical Mythology of the Two State Halls—Persepolis and Ali Qapu as a source of mythological narratives underlying the motifs and architectural structures of Iranian heritage.

This book, in three parts, first introduces Georg Friedrich Creuzer—the founder of the earliest method of mythology—and his approach, namely allegorical mythology; then, in the following two parts, the state halls of Persepolis and Ali Qapu are analyzed through this method. The latter two sections are, on the one hand, rich in mythological narratives along with the motifs, visual symbols, and architectural structures associated with them, and, on the other, filled with numerous references to the cultural connections among the mythological traditions of Iran, India, Turan, and Mesopotamia. Among these, the myth of the Tree of Life is examined from various angles within the mentioned cultures, with its motifs and visual symbols analyzed in detail.

Presenting the book as a valuable source for exploring the narratives of the Tree of Life, Mr. Akhoondi posed several fundamental questions about the story of the Tree of Life during the Safavid and Achaemenid periods, and invited Ms. Nastaran Hashemi to discuss the mythological narratives of the Tree of Life in Iranian culture.

Ms. Hashemi began by addressing the foundational role of plants and trees in the Indo-Iranian worldview, explaining that in this culture, plants are not only symbols of life, but the earliest ancestors of humankind were also envisioned in plant form. This is why the Tree of Life has always held a special place in the various arts and historical periods of Iran. She then referred to the myth of Mithra’s birth from a plant—a lotus flower—and the tale of Mithra’s bull-slaying, in which he scatters his share of the sacred drink soma upon the earth so that all living beings might be created. In a later version of the story, after killing the bull, stalks of wheat and grapevines grow from its blood, giving rise to all creatures—thus, not only Mithra, but all living beings originate from plants.

Ms. Hashemi then moved to later versions of the Tree of Life myth. In the Mazdean narrative, Ahura Mazda creates, in order, the sky, water, earth, the first plant, the bull, and Keyumars. After Ahriman’s assault, the plant, the bull, and Keyumars are all destroyed, and in their place the sacred Harvisp-Tokhmok tree is created in the midst of the Farakhkart Sea. This tree contains the seeds of all plants, and whenever the Simurgh alights upon it, the seeds are scattered as it takes flight, to be carried by rain across the earth—thus giving rise to all vegetation. Beside this tree grows another, Vispobish, symbolizing healing, with a remedy for ten thousand diseases. After the destruction of these two trees, the Gokarn tree comes into being. To destroy it, Ahriman sends a toad/lizard into the sea, and Ahura Mazda creates two guardian fish to circle its roots endlessly, so sensitive that they can detect the slightest change in the water.

Continuing with the Tree of Life narratives in Iranian tradition, Ms. Hashemi cited the myth of Mashya and Mashyana, in which the first man and woman—bearing farr (divine glory) between them—are born from the seed of Keyumars, which had transformed into a rhubarb plant, thereby bringing forth the human race. She also recalled the tale of Siyavash’s metamorphosis into an evergreen plant called Parsiavashan, resembling a cypress and symbolizing the Tree of Life.

She further traced the Tree of Life motif in stories related to Zoroaster. In the first, Zoroaster immerses himself in the Daiti River before his calling, and, once purified, meets the Amesha Spentas. At that moment, he gazes upon the world from a mountaintop, seeing it divided into four quarters, each filled with plants and trees. In another account, Zoroaster approaches King Goshtasp carrying the sacred Avesta texts, a flame of fire, and two cypress branches—one of which is later planted in the Borzin-Mehr Fire Temple.

In closing, she addressed the historical aspects of sacred trees such as the plane tree and the golden vine in Iran. According to one story, in the dream of Astyages, king of the Medes, a vine grows from the womb of his daughter Mandane, spreading to cover all of Asia—a vision interpreted as foretelling the rise of Cyrus and his dominion over Asia. Other accounts tell of golden vine and glowing plane tree ornaments in the Achaemenid royal palaces, including the gift of a golden vine and a radiant plane tree to Achaemenid kings, and Xerxes’ reverence for these offerings. Finally, Ms. Nastaran Hashemi concluded her talk with an etymological study of the words Pars and Pasargad, which, in Sanskrit, refer to plants such as the plane tree and the grapevine, as well as the places where they grow.

After Ms. Hashemi’s presentation, Mr. Akhoondi introduced the book Psychological-Mythological Approaches to Art as the source for the “analytical mythology” method, and spoke about Gilbert Durand, the founder of this approach. He noted that this book examines the works of major artists from Iran and around the world through ten different psycho-mythological methods, three of which were developed by Durand himself. One of its chapters focuses specifically on the analytical mythology method.

Mr. Akhoondi then discussed Durand’s perspective on the deep connection between imagination and myth, and, posing several questions about the concept of the Tree of Life and why the tree was chosen as a symbol of life among Iranians and other cultures, invited Ms. Saina Mohammadi Khabazan to analyze Tree of Life using this approach.

Before beginning her talk, Ms. Khabazan thanked the organizers and spoke about the importance of turning to cultural and artistic activities during difficult social conditions, describing the Sohrab sessions as a refuge for people of culture and art. She then introduced her topic: exploring the mythological narratives referenced in Ms. Sharifi’s Tree of Life and the underlying meanings—whether consciously or unconsciously—portrayed by the artist.

She outlined the theoretical basis and structure of her analysis, explaining that in Durand’s analytical mythology, the focus is on how myths are formed, starting from the earliest sparks in the human mind. From Durand’s perspective, myth formation passes through the realm of human imagination. When confronted with a fundamental threat—such as death—if humans cannot resolve it in reality, their imagination becomes active, eliminating the threat in the realm of fantasy. This process, he argued, is the very formation of myth.

Durand described five stages in this process: reflection, force, archetype, symbol, and myth. In the first stage, the human mind produces reflexes to meet vital needs; if these reflexes cannot solve the problem in reality, they become an inner force (second stage). From this force arise primordial images, which take the form of archetypes (third stage)—universal and timeless images. When such images are given a specific time and place within a culture, they become symbols (fourth stage). Finally, when these symbols are embedded in a narrative, they become myths (fifth stage).

For example, the fear of falling from a cliff (leading to death) may produce a force within the human mind to prevent such a death. This force can manifest in archetypes like the mountain, the tree, or wings. Among Iranians, these can culturally transform into the symbol of the Simurgh, leading to the myth of Zal and the Simurgh.

Ms. Khabazan explained that to apply this method to a work of art, one must first identify the mythological narratives behind the piece, then trace the symbols, then the archetypes, then the formative forces, and finally determine how all of these originate from a particular reflection.

Analyzing Tree of Life, she identified multiple Iranian mythological references:

- The First Plant, depicted as a tree in boundless waters.

- The Harvisp-Tokhmok tree, with seeds shown falling from it.

- The rhubarb plant in the myth of Mashya and Mashyana, here portrayed as a bifurcated tree with farr (divine glory) emerging from between its branches.

- The lotus birth of Mithra, with farr rendered as the sun—Mithra being the solar deity in ancient Iran—now rising from a plant.

- Most importantly, the Gokarn tree, with two fish and a lizard at its roots.

Reviewing each of these myths, she noted that together they symbolize creation (of all beings, plants, humans, and divinely gifted humans), fertility, and the continuation of life. Moving to the archetypal level, she sought a universal, cross-cultural pattern for creation, fertility, and life—not tied to a specific Iranian mythological tree like Harvisp-Tokhmok or Gokarn. This led her to the archetype of the Tree of Life, an ancient image of a cosmic tree, the axis and pillar of the universe.

Exploring the force that shaped this archetype across cultures, she pointed to humanity’s fundamental drive toward life and its continuation, expressed through plants. Plants are ideal vehicles for this image because of their annual fruiting, regeneration after winter, and ability to grow in harsh conditions. In other cultures, however, this role is sometimes played by animals—for example, the bear in Nordic cultures (because of hibernation) or the snake in Mesopotamia (because of shedding its skin).

Finally, she examined the initial “reflection” or primal origin of this force and need. Broadly, it arises from the human response to mortality. Unable to overcome death in reality, humans turned to imagination, envisioning eternal life in the archetype of the Tree of Life. More specifically, she explored the meaning of “plant” itself—its root giyah in Persian meaning “alive,” related to Gokarn (“living fighter”) and Keyumars (“mortal living being”). Likewise, “tree,” “dar” (Persian for tree/wood), “daru” (medicine), and the English tree, drug, and dry share a root meaning “dried plant,” dating to the era when humans discovered medicinal plants. This was the agricultural age, when plants became both nourishment and salvation for humankind—experiences that entered the collective imagination as archetypes, symbols, and myths.

She contrasted this with cultures such as Mesopotamia, where this role was played by animals—haywan (“alive” in Arabic)—serving as life-sustaining agents in myths from sacrificial rites to crossing the Bridge of Judgment. In contrast, in Turanian mythology, the Tree of Life goes beyond the concept of life and its continuation, forming the very skeleton of the cosmos in fifteen layers, with branches in the upper realms and roots in the lower realms, and playing a key role in stories of human origin and death.

In conclusion, Ms. Khabazan suggested that Ms. Sharifi may have chosen the Tree of Life theme in response to today’s societal conditions. Referencing the depiction of the slain fish in the artwork, she proposed that perhaps, in our current difficulties, the reason we are not living with zest and are more preoccupied with death than life is that the protectors of life have been defeated—the lizard has triumphed over the fish—and the Tree of Life is under threat instead of flourishing. One day, she hoped, the artist might paint a blossoming tree with victorious fish.

After Ms. Khabazan’s presentation, Mr. Akhoondi introduced the book Homonrans: Archaeo-Mythology of Narrative as the source for the “archaeo-mythology” method. Developed by Esmaeil Gezgīn, this approach combines material evidence and symbolic evidence in an interdisciplinary method bridging mythology and archaeology, seeking to understand not only how myths were constructed but also why they were constructed in a particular form.

Mr. Akhoondi then posed a series of questions: given that in the artwork a tree has grown from the head of a demon, if the Tree of Life is destroyed, is it possible for it to grow again at the hands of the very being that destroyed it? Why, in this work, is the demon depicted instead of the lizard? What is the relationship between the sun (farr) and the demon? And with the death of the fish and the victory of the lizard, the demon, Ahriman, and evil—what should be done, and what is our responsibility? He then invited Mr. Behrooz Avozpour to analyze Tree of Life using the archaeo-mythology method.

Mr. Avozpour began his talk by thanking the Peydayesh Research Group, the Mit-Okhteh Center for Mythological Studies, the Iranian Book Illustration Institute, Lajvard Gallery, and Chaghalash Consulting Engineers Company for organizing the session. He described Ms. Samaeh Sharifi as a socially engaged artist—one who compels people to think, something he feels is deeply lacking in contemporary Iranian society, where art and culture have the potential to bring about change. He invited all like-minded artists whose work references myth to submit their pieces to the Mit-Okhteh Center for consideration in future Sohrab sessions.

Referring to Homonrans, Mr. Avozpour emphasized the importance of material evidence alongside symbolic evidence, noting that material evidence helps dispel biases regarding symbolic interpretations. Gezgīn’s perspective is that, at a certain point in history, humans—upon recognizing their own mortality—sought to create narratives that would outlast them, thus making themselves, in a sense, immortal. He identifies three historical turning points in human narrative-making:

- Cosmos-building meta-narratives: myths explaining the creation of the universe, rooted in a belief in life after death, and defining humanity’s place in the cosmos. For example, the Turanian Tree of Life—mentioned earlier by Ms. Khabazan—belongs here, as a cosmic tree supporting the entire world.

- Culture-building meta-narratives: myths explaining the formation of culture, historically tied to humanity’s shift from nomadic hunting to settled agriculture, leading to urban life, civilization, norms, and taboos. The Iranian Tree of Life, which both sustains life through nourishment and protects against disease and death, falls into this category.

- Separating meta-narratives: myths that divide humans from other beings—or from other humans—based on arbitrary criteria such as skin color, ethnicity, race, or religion. The division of the world among Fereydun’s three sons is one such myth. Mr. Avozpour remarked that modern Iran is in this stage, with a social mindset more focused on identifying “who is not with us” than “who is with us,” fueling ethnic and sectarian disputes.

Mr. Avozpour then compared Tree of Life with its underlying myths, noting differences such as the depiction of the sun instead of farr, the lotus instead of the rhubarb plant, the demon instead of the lizard, the replacement of a happy ending with a tragic one, and the emergence of a new tree from the head of the demon intended to destroy it. He suggested that, because of these changes, the Tree of Life—which originated in a culture-building meta-narrative—has been placed within a separating meta-narrative, with an emphasis on dualities such as demon versus deity, or Mithra versus the bull. In other words, new elements have been added that belong to the separating meta-narrative.

He asked whether this alteration was a conscious, creative choice or the result of misunderstanding the myth. To explore this, he outlined four possible relationships between art and myth:

- Myth-avoidance – the most common approach in Iranian art, avoiding direct engagement with myth.

- Myth-stripping – presenting a myth but removing its mythological elements.

- Myth-making – creating a new myth or narrative.

- Myth in art – faithfully reproducing a classical myth.

Mr. Avozpour ruled out myth-avoidance and myth-stripping for Tree of Life, since it contains numerous mythological elements like the fish and the demon, and also excluded “myth in art” because it does not replicate an existing narrative exactly. He concluded that the painting belongs to the third category—myth-making—as it creates a new story.

Turning to the question of creativity, he cited Ibn Sina’s Al-Isharat wa al-Tanbihat, which identifies three types of artistic creation:

- Transference or theft – a direct, uncreative copy.

- Creation ex nihilo – philosophically impossible, as all works are built upon pre-existing texts and contexts.

- Adaptation with creative transformation – the essence of artistic creation.

Drawing on Nasir al-Din Tusi’s Asas al-Iqtibas, Mr. Avozpour explained two forms of adaptation: the traditional, mechanical borrowing (equivalent to transference) and the true, inspired adaptation—literally “taking fire” from another source. In older times, fire was not easily made; one had to obtain a live ember from someone who already had it. This “taking fire” is a metaphor for how an artist, struck by a powerful experience or work, produces a new creation.

He pointed to Ms. Sharifi’s own account: the sight of shrouded infants in Gaza had such an impact on her that it sparked the creation of Tree of Life. He gave examples of famous creative adaptations, such as Freud’s Oedipus complex (adapted from the Oedipus myth) and its reworkings by Pamuk in The Red-Haired Woman and Baraheni in Old Boy, Duchamp’s reinterpretation of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and Barthes’ S/Z, adapted from Balzac’s Sarrasine.

In closing, he characterized Tree of Life as the product of inspired adaptation: a work rooted in the Tree of Life myths, yet infused with the artist’s personal vision. It is a multi-layered, socially engaged, and creative piece that transforms ancient myth into a new narrative—one that provokes questions in the viewer: Why the demon? Why the tragic ending? Why the rearrangement of symbols? These unanswered questions, he concluded, are proof of the work’s creative force.